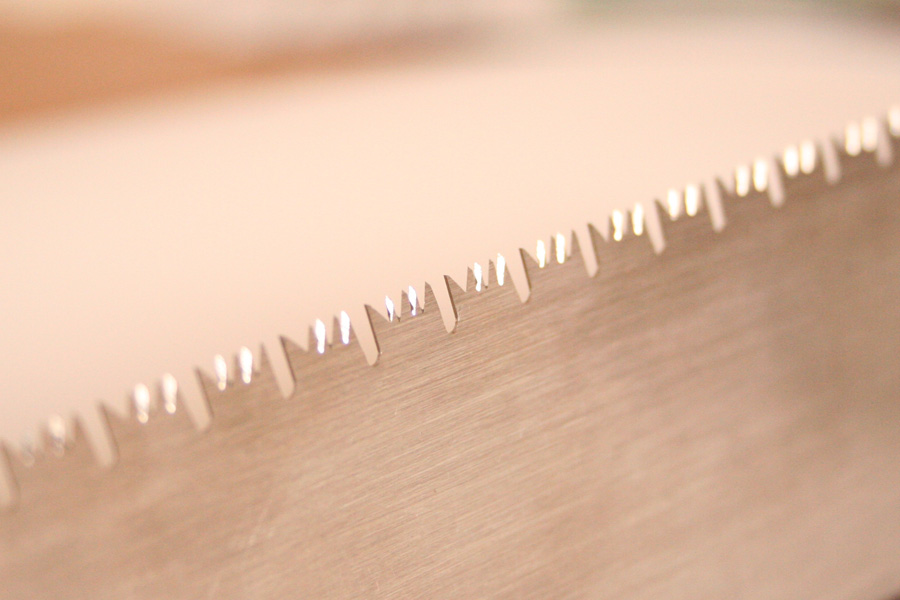

I was sharpening the biggest kanna blade I have when the killer stuck on the stone. Like those japanese guys who leave the blade standing on the stone, holding only by surface tension or electromagnetism, who knows, and go for a coffee.

Anyway, the blade was standing there, I wanted to take a picture so you believe me, then the blade falls, hand goes for it, then I go to the hospital. Fun, fun, fun.

This was last week.

So no woodworking, no sharpening and no work. I could not even properly walk friday.

The finger is fine... no bone was cut and no infection. You don't want the details anyway. Flash forward till today.

Julia was talking with a friend from Germany today, and after finishing she comes to me and asks: "am I getting stupid?" Fair question, since we have been getting rid of books like the military after a coup. The thing is, we don't really read anymore and most of the talk is sewing machine in one room and hammer and plane in the other. We watched yesterday a movie of Godard, but that almost doesn't count as intellectual anymore.

I had the same question a while ago. You know, I'm a post-doc, and I'm supposed to research and learn... they pay me for that. But to be honest, scientifically speaking, last 2 years were an infinite desert. ( I have my reasons for that, not least that I sincerely think that trying to solve global problems with the same method that brought us here is at best wishful thinking a la middle ages, and at worst, a suicidal neurosis.) One year of vacations and one year of doing what I know how to do... not really learning something new in my job.

But the thing is, I don't feel

at all that I'm getting dumber. (Save the finger cut that is.) What I've been doing during the last 2 years in my free time is: a) to study parts of the world, b) develop the methods to interact in a proficient way with those parts of the world, and lately thanks to Jason c) communicate in a thoughtful way the invariants I find in the parts of the world I study. Granted, to study the steel of one of my blades and how it interacts with the grain of a stone, and after that how it goes searching the molecules of the wood are not going to get me a nobel prize... but then again, you don't do science for the results, you do it for the sake of it.

What happens when you learn a skill? Say blacksmithing. When you learn to forge a knife, what your body is doing is learning facts about the world. How the blow of the hammer creates a certain deformation on the steel, which is dependent on the temperature, the kind of material, the angle at which you hit... you are learning facts about the world that permit you to move in an assertive way in the domain of hammering metal.

This is a knowledge that cannot be put in a formula, and that's why our modern world seems so poor at times, for we value more the formula than the metaphor. This is a knowledge that has to be embodied, that is, lived. And this is at odds with pretty much the whole of modernity.

And so this plane came to be.

I started it last year in Celle, from some maple Opa had laying around. I finished the fourth wedge today. The first two were crap, the third one made out of spruce and sincerely cheap... This one is

nice. I just didn't have the accuracy to make a properly fitting one six months ago. I didn't have the understanding necessary to access the world of plane making and move comfortably there, even with a wounded finger.

She will remain here in Europe, hopefully helping a friend with his bike shop in Leipzig.

And that's it, really. When Benjamin declared the death of the work of art's aura in the age of mechanical reproduction, the only thing you need is to do, is to produce in a non-mechanical way, and you get the aura back. It's that plane with the knot on top, and the ash wedge, and the gouge marks on it. There is an intimacy born from the experience, the experience of the close contact with the material, that you cannot buy, that you cannot exchange.

We knew this, and we can learn it again.

When Rilke sadly wrote that “for our grandparents a ‘house’, a ‘well’, a familiar tower, their very clothes, their coat: were infinitely more, infinitely more intimate; almost everything a vessel in which they found the human and added to the store of the human”, and continued then complaining of the lifeless things imported from America, Marx should have come by and said: "it's the means of production, idiot."