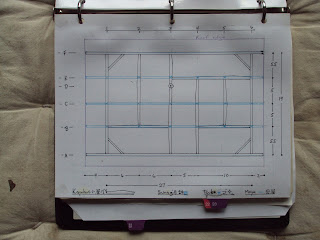

Break 20 and you are creating the Gonzalez™Universal Random Matrix tooth pattern. Created by your humble blogger (did you know that in germany blogger is a clothing style too?) myself.

The Gonzalez™Universal Random Matrix saw consists of gullets arranged in the same pattern as the first 12 eigenvalues of a random matrix. It's like the Fibonacci series but cooler and made precisely to cut well. It also solves the basic levels of an hydrogen atom when the chromodynamics equations are taken into account.

It also presents a carefully filed curve in the top part of the saw that both dissipates heat while cutting and compensates the movement of the hand at the end of a stroke

Let's see it closer

The depth of the gullets follow a catenary function to improve sawability

Here is the dissipation zone

It does cut like it is expected from a Gonzalez™Universal Random Matrix saw, as soon as Julia brings her Ipat i shot a video of it.

All this thanks to 1 single sided file I found in my box. Man they are sweet for dozuki. I used to think dozuki were difficult to file. I was simply using the wrong tool.

On the other news I'm moving to Valpo for a few weeks, second carpentry course will have sushi it seems. I'm building the structure from the previous exercise and taking Keiran with me to continue his apprenticeship

I also made a dai sunday, but chilean roble doesn't have "rays", is the one on top without sub-blade. The endgrain

We also thought about acacia, but no rays either, extremely hard though. (Also, the left side is planed, the cuts directly from the dosuki I sharpened today.)

American oak does but I don't like it

Japanese white oak

more

some other wood, more metallic, for a blue paper steel blade

And I've been making some handles of old smelly oregon pine (or something like that)

EDIT:

In case you ask... I bought the dozuki originally form fine-tools, before moving to Graz. I tried to make a bed in douglas fir with it, construction market lumber. Then it broke. The saw can be found here:

Shirai Sangyo Dozuki however, after seeing more carefully how I broke the teeth, like 90% of them broke on the same side, which indicates to me that the set was not properly made in this saw.

If you want to get one, bring me a dozuki, a single sided file, and a few beers. Let's say 30 litres. Or 20 litres and 5 kilos of meat that you need to bbw while I file.

Now, if you don't think on visiting chile in the near future, you always can get one from nagakatsu, but he doesn't have the random matrix pattern. Take a look:

http://www.mitsurouwax.com/nagakatsu/doutsuki1.html

Another option would be to make a small workshop in Germany during October, not in Munich though, too many drunkards and too close to the Reich in October. In Celle instead. Saw vice making, saw sharpening and madonoko making. I got 34 hits from Germany last week so I guess somebody over there is reading this. Wir konnen ein kleines bischen Deutsch, and I guess Julia would be trilled to work as a translator. Shall I put an ad somewhere?